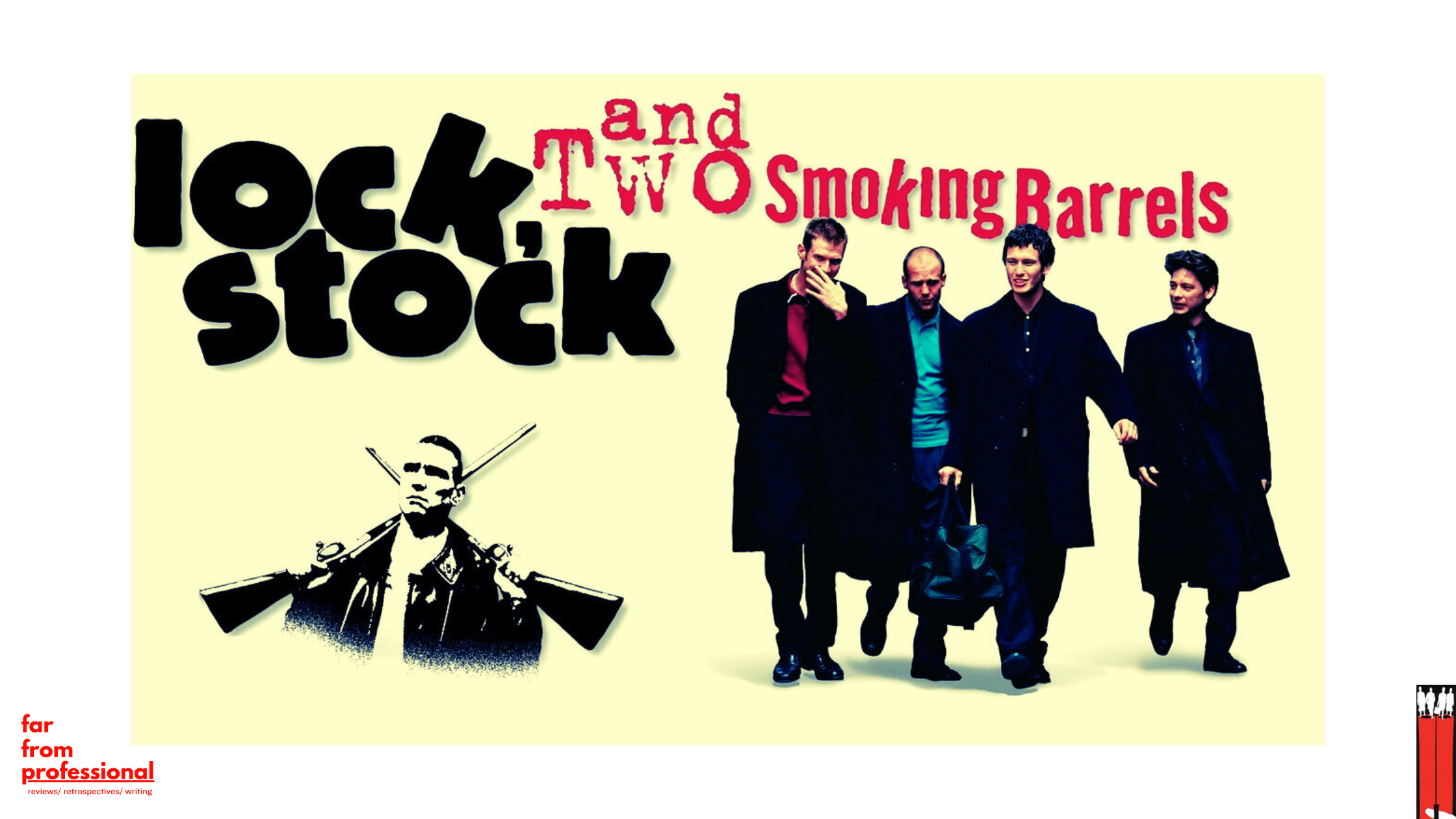

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels

Vinnie and the boys in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998).

Guy Ritchie’s 1998 film debut is a spiritual successor to Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and represents the fearless filmmaking of the 1990’s in a fantastically raw, and gritty criminal dramedy that has few equals.

The opening of any film sets its tone, and from the first scene, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels prepares the audience up for an onslaught of dialogue that explodes like a stick of dynamite. Guy Ritchie’s way of storytelling hooks the audience from the beginning. As the opening credits roll, we meet “Bacon,” a rough and tumble criminal, played by Jason Statham, hocking stolen goods on the streets of London. His partner in crime is Eddy, a card shark with a penchant for seeking out dangerous opportunities. Bacon sets up shop on a London street corner while Eddy acts as both lookout and interested customer. Richie’s dialogue screams through Statham as Bacon releases a deluge of snappy one-liners and sales pitches that tickle the ears of passersby and instantly engages the audience. “Anyone like jewelry? Look at that one there – handmade in Italy, hand stolen in Stepney. It’s as long as my arm, I wish it was as long as something else.” Visceral visuals and snappy conversation push and pull Richie’s film in and out of your senses with the stylized sophistication of a mob boss performing open heart surgery.

Bacon and Eddy’s sidewalk sale ends when the cops (cozzers) show up. The duo dumps their stolen goods into a suitcase and takes off as the soundtrack sizzles with Ocean Colour Scene’s “Hundred Mile City”.

Richie’s razor-sharp script and mad visual presentation are uplifted to new heights with its soundtrack. Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels musical score competes hand-in-motherfucking-hand with Tarantino’s Jackie Brown and its soulful blend of 1970’s era music. Composer John Murphy nails down the music with brass tacks here and would go on to score some of the UK’s cinematic masterpieces, like 28 Days Later and Snatch.

The entire movie is pushed along by Alan Ford’s third-person storytelling narrative. Ford has a small part in this movie as a bartender but would become infamous through his role as Brick Top in Guy Richie’s second film, Snatch, in the year 2000.

Ford’s cadence adds another layer of paint to this British blockbuster as he introduces sordid characters and voices their inner monologue throughout the film in a similar vein to Scorsese’s freeze-framed moments in Casino. The story of Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels is never dropped on its head during these voice-over sequences as they enhance the film’s pacing, world building, and character arcs. The plot also gets a shot in the arm from Ford’s narrative which makes this one of the easiest crime films to follow; taking off like a rocket when Eddy spies a lucrative opportunity.

Eddy’s talent with cards has caught the attention of Bacon and their two friends, Tom and Soap. Soap, played by Dexter Fletcher, is an honest chef who doesn’t dabble in any crime while Tom, played by Jason Flemyng, loves to submerge his entire being in nefarious activities. Eddy has convinced the lot to each donate $25,000 so that he can play cards with “Hatchet” Harry Lonsdale, a local crime boss played by P.H. Moriarty. The four friends are so confident in Eddy’s gambling abilities that they see no danger in playing cards with a man who has a penchant for beating people to death with sex toys…c’est la vie.

The plot thickens when we learn that Hatchet Harry is going to rig the card game so that Eddy is forced to give up his dad’s bar – Harry wants to expand his empire and will cheat to do so. Thanks to his colleague Barry “The Baptist,” played by the late Lenny McLean, there are few obstacles that will stand in their way. While we learn about a crooked card game, we are introduced to a group of pot growing hippies and a troupe of thieves who specialize in robbing drug dealers. These college “puffs” are happy growing marijuana for Rory Braker, a mad man with an afro who runs a ruthless Black gang in London’s East Side.

Unfortunately for them, a gang of thieves led by a ruthless man named Dog has eyed their lucrative operation. The criminal underworld is poised to run into each other like an errant locomotive, and Richie is the mad conductor with a death wish, racing a line of cars loaded with plot twists off the rails, and slamming them against the big screen. Linking all these sordid lots together is Chris, a debt collector who works for Hatchet Harry. Played by Vinnie Jones, Chris is the flying bullet that crashes through every set of characters, cauterizing entry and exit wounds and binding them together into a seamless mass that accelerates the plot from a calm and interesting beginning to a frenetic and chaotic finish. Vinnie Jones hammers the role of Chris home with a nine inch coffin nail that was forged in Hell itself.

On paper, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels sounds complicated and confusing, but as Tom would say, “it’s kosher as Christmas.” The script slides along the reels like a gravy train with biscuit wheels, never once running into a hiccup that distracts the viewer or threatens to bore them. The film is also one that highlights London’s East End, a notorious region that is home to the sing-song language known as Cockney. The rhyme and dance of Cockney is on full display with Barry the Baptist, Rory Braker, and Tom. The dialogue sizzles because of its inclusion, and while it may seem esoteric to the outside world, it adds another layer of originality that piques the interest of the viewer. Cockney was the voice of London’s brutal East End and the gangsters that called it home. From the Kray twins to the Peaky Blinders, this region has produced more notorious gangsters than any other part of London, and its disappearance makes its inclusion in Richie’s films all the more poignant—preserving and exalting a by-gone era of British culture.

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels is standard issue watching for any moviegoer who loves a good crime flick. The grit and grime that pours off the screen is reminiscent of Steven Soderberg’s 2000 drug drama, Traffic. A filmmaker’s vision must be unique and compelling, and like Soderberg, Richie delivers a fantastic storytelling vehicle with his 1998 debut. British crime-dramas, feature, or series, owes their warm reception to Richie’s film debut. Tarantino’s influence has reverberated across the world, but only a few writers and directors have managed to bottle that lightning, and Guy Richie is one of them.